The Bumz

The Bumz

Based on the Straight Outta Fresno: From Popping to B-Boys and B-Girls project and Straight Outta Fresno's archive.

Text and archival material curated by Colin Burch

The Hmong:

To understand how a group of predominantly Hmong youth ended up doing headstands and airflare in 1990s Fresno, you have to understand the recent history of Hmong migration. The Hmong are an ethnic group with roots in China and Southeast Asia. During the Vietnam War, the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) secretly recruited and trained Hmong living in Laos to help the United States in its fight against the North Vietnamese Army. Following the United States’ defeat and eventual withdrawal from Southeast Asia, the Hmong community and their families in Laos feared local repercussions for helping the Americans with many looking for ways to leave Laos. A small group were lucky enough to be evacuated to the United States at the war’s end; however, many others made their way to refugee camps in Thailand with hopes of eventual resettlement in other countries such as the United States, Canada, France, and New Zealand. Escape to these camps was often harrowing and occasionally deadly; once in the camps, Hmong families endured harsh conditions and long waits for potential relocation to western nations. In the United States, resettlement was determined by American sponsors, often private agencies and religious organizations who bore some of the perceived economic burden. While the United States government deliberately tried to disperse Hmong refugees throughout the country, two main areas attracted Hmong refugees due to established support systems and networks of families; these two areas are Minnesota’s Twin Cities, Minneapolis-St.Paul metropolitan region and Fresno, California.¹ Fresno went from having one Hmong family in 1977 to a population of over 35,000 Hmong by 2019.²

The majority of Hmong settled in working class neighborhoods throughout Southeast Fresno where they continue to experience higher rates of poverty than almost any other ethnic group in the United States. As unskilled agrarian workers, Hmong refugees found few resources and opportunities to make ends meet. Despite these troubles and being geographically scattered, the Hmong have retained a strong sense of identity and a tight-knit culture. Hmong culture and community are on vibrant display each year at the Hmong New Year Festival at Fresno Fairgrounds, which is full of traditional Hmong clothing, food, and entertainment. Over 120,000 people attend annually from all over the world. Fresno's Hmong New Year Festival is the largest overseas gathering of Hmong in the U.S.³ In recent years, amidst the brightly colored traditional Hmong clothing with its characteristic Paj Ntaub style of embroidery, vender booths selling everything from traditional Hmong Xauv necklaces to Hmong karaoke DVDs, and the inviting scents emanating from Hmong food stalls, one might also hear a funky Clyde Stubblefield drum break escaping the auditorium hosting hundreds of Hmong (and non-Hmong) b-boys and b-girls battling for crew supremacy.

The first generation of Hmong b-boys were the children of Secret War refugees. Without a Hmong country to call home, many grew up ambivalently caught between the trauma of their parents’ refugee experiences and their own challenges that came with growing up as working class youth of color in Southeast Fresno. Among other things, Hmong youth contended with gangs and street violence, harassment from law enforcement, anti-immigrant views from their neighbors, and flat out racism all while feeling pressure to maintain Hmong cultural traditions and stay involved in the local Hmong community. However, through hip-hop culture, Hmong b-boys in Fresno navigated these impediments and found purpose, place, and identity.

In hindsight, it is not remarkable that hip-hop appealed to these youth. During the 1980s and through the 1990s, hip-hop culture gave voice to marginalized populations throughout the United States. More to the point, hip-hop culture was accessible; like many of their working class contemporaries across the nation, Hmong b-boys learned and mastered their craft not in expensive dance studios but in free public spaces across Fresno including parks, community centers, high school lunch gatherings, and local garages. What is remarkable is the extent to which hip-hop culture became embedded within Fresno’s Hmong youth, despite Fresno’s isolation from the hotspots of hip-hop such as the Bronx and Los Angeles. In their oral histories, Bobby Bliatout and David Yang, founding members of Fresno’s first known Hmong b-boy crew, shed some light on how and why Hmong youth gravitated towards hip-hop culture in general and b-boying in particular.

The Bumz

Formed in 1992, the Bumz are the first known Hmong b-boy crew in Fresno. The group consisted of several Hmong teenage boys who were close friends. At first, the Bumz identified as house dancers and called their dancing “housin,” a more stylized, party-oriented type of dancing that included lots of waving, popping, and up-dance. They adopted the name the Bumz after one of their crew members began telling girls that their style was BUM style, explaining that BUM stood for Busting Unique Moves.

Impressing girls was a huge motivation for joining a b-boy crew. Another motivation was to have a group of friends that had your back in dicey neighborhood situations. In the Bumz, Hmong youth were able to congregate together and express themselves as children of refugees with a shared history and culture, where they were, at least momentarily, not outsiders. In their oral histories, both Bobby Bliatout and David Yang credit the Bumz for helping them stay away from street gangs. “It saved my life. It really did. It saved my life,” says Yang in his interview. At 15 years old, Yang joined a gang and ran away from home. After a random street attack, a drive-by shooting, and a car accident that hospitalized him, Yang moved back home and traded gang life for dancing. Bliatout states in his interview that the Bumz had a firm rule that they would not ever become a gang.

This first generation of Hmong b-boys had no teachers. Since Fresno was cut off from all of the major hip-hop scenes located in bigger cities like New York and Los Angeles, the Bumz relied on themselves and the few breakdancing movies they were able to get their hands on, such as Breakin’ and Beat Street. They practiced and performed their dancing wherever they could, including parks, community centers, the Hmong New Year Festival, Fashion Fair Mall, and schools such as McLane High School among others. They also practiced in the living rooms and garages of their parents’ homes where they were increasingly relegated to as gangs and police harassment pushed them out of public spaces. Thus, the Bumz had to adapt their dancing to a variety of environments and increasingly tight spaces. Since smooth surfaces are a must for breakdancing, it was a common practice for b-boys to keep a piece of linoleum or cardboard in the trunk of their car.

When b-boy crews compete against one another, they refer to it as a battle. Battles run the gamut from formal, organized events, to on-the-spot “call outs” at the local park. Battles are where b-boys and b-girls test their skills, show off the moves they have spent hours working on, and where they build community. In short, battles are an essential aspect of b-boy and b-girl culture. In part because they were one of the first crews in Fresno and in part because they were not particularly plugged into larger regional and state battle scenes, the Bumz were mostly limited to local battles against other Hmong crews in Fresno such as the Smurfs, who were the second Hmong b-boy crew in Fresno and consisted of some of the little brothers of the Bumz. However, Bliatout also recalls battling a crew of predominantly white and Hispanic kids called Zoomies Dimensions as well. Battles were coordinated by word-of-mouth and frequently occurred in schools. The key to winning a battle was to outperform the other crew in athleticism and creativity. It wasn’t enough to simply execute power moves such headspins, airflares, and windmills; they had to add style to the move and make it their own. Ultimately, battles were not high-stakes but they were a place for Hmong to gather together, build networks, and learn from each other. It also served as a nonviolent way to workout grievances.

Despite being limited to the local battle scene, the Bumz built a reputation as talented performers and started picking up gigs performing at universities, talent shows, and even the Hmong New Year festival.

B-boying as Identity

One of the most meaningful acts of being a Hmong b-boy was the choosing of a b-boy name. In many ways this served as an individual expression of one’s own identity. For example, David Yang’s name was “Handy-Smurf,” reflecting that he was an artist who liked to draw and was involved in establishing the Smurfs Crew. Bobby Bliatout’s nickname was “Stroll,” while other names included “Veal,” “Boony,” “Flago,” and “Wayno.” The adoption of these hip-hop alter egos also meant a temporary reprieve from the complicated histories associated with their Hmong family names. In a world where “Yang” and “Bliatout” elicited awkward stumblings from substitute teachers, and questions like “where are you really from,” the act of creating your own identity is a defiant statement of belonging. Other b-boys and b-girls get the Handy Smurf reference and know what it means to Stroll and care more about how clean your six-step is than where your parents came from.

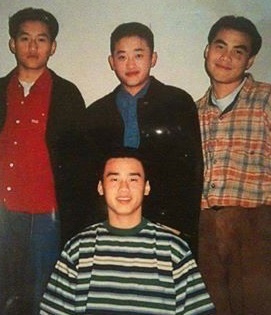

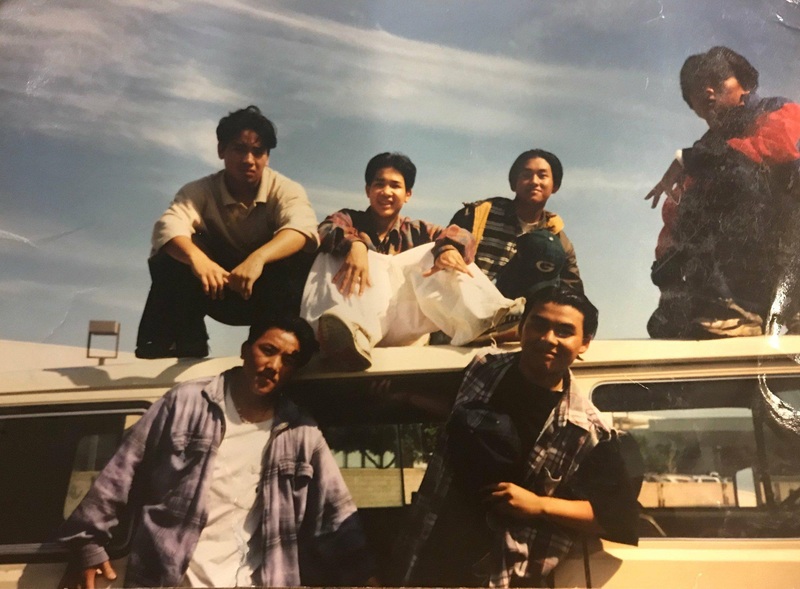

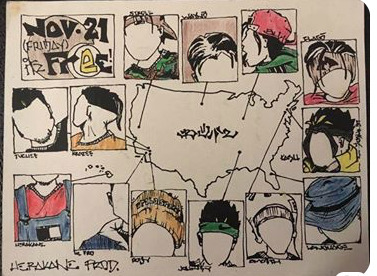

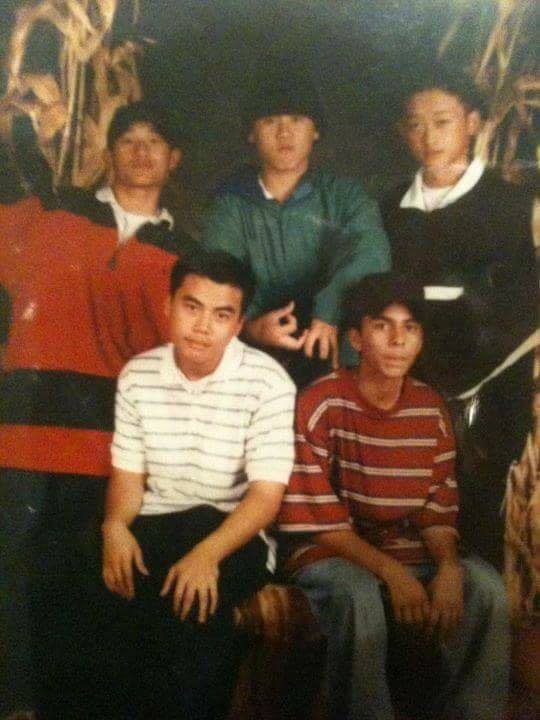

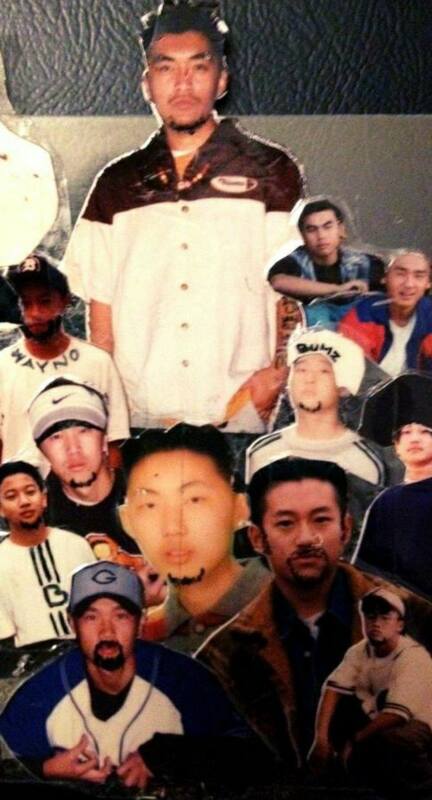

The Bumz always worried about getting too big, so they deliberately restricted membership. The Smurfs Crew (which included younger brothers of Bumz crew members) hoped to join the Bumz but were denied. However, the two crews affiliated with each other and had some overlap. In addition, not all members of the Bumz were strictly breakdancers. Some were also rappers, DJs, taggers, or artists, such as Yang, who specialized in graffiti-style art. Flyers, such as the one in this exhibit, display some of their skills and tell us more about the Bumz. The flyer is advertising a free performance. There are caricature depictions of each crew member with their b-boy name and a line pointing to where they are originally from in the United States. While many of them are originally from Fresno, the majority are not. Bliatout lived in Bakersfield as a young child and Yang is from Honolulu. Yet, despite these disparate origins, Fresno’s existing Hmong population and networks clearly drew their parents to settle in the Central Valley. In this sense, flyers like this map and represent the broader Hmong community as much as they represent a specific event. The flyer also displays some of the prominent Bumz fashion trends, including baggy clothes, backwards and bucket hats, and headbands. Another graffiti-style drawing of the Bumz shown here below also emphasizes their fashion choices and noticeably features each member in a unique pose. These fashion styles and poses are further represented in the crew photos included in this exhibit, particularly the photo in winter jackets and the photo on top of a car. In short, the Bumz saw themselves as members of hip-hop culture rather than strictly as b-boys and expressed that identity both by participating in multiple hip-hop elements and dressing the part.

The Bumz will be remembered as the first OG Fresno Hmong b-boy crew. They paved the way for the next generation of Hmong b-boys such as the Smurfs, Dancing in Style (DIS), and the Wizards. Given the tight-knit nature of the local Hmong community, it is not surprising that many members of the new crews were siblings of Bumz crew members who learned from and looked up to their brothers even as they worked to improve upon their techniques and destroy them in battles. While proudly boasting that he and his crew mates surpassed the Bumz in skill level, Ville Thao, a Smurfs Crew member whose brother was in the Bumz, describes how he looked up to the Bumz as a youth while watching them battle across the city. Once Thao and his Smurf crew mates transitioned from hunter to hunted as new crews like the Wizards and Climax (see our exhibit on the Climax/Soul Control Crew) hit the scene and challenged them, they carried kinetic samples of the Bumz with them in the moves they deployed in battle. In other words, while the Bumz mainly kept to Fresno, the crews they inspired, trained, and mentored in and around the Central Valley carried the Bumz name with them as they ventured beyond Fresno while making names for themselves in larger scenes such as Orange County and the Bay area. Even more directly, both Bliatout and Yang have also passed dancing on to their children. One of Yang’s daughters is a hip-hop dance teacher and another of his daughters is in her own crew.

Scholar Sean Slusser describes the overall importance of Hmong b-boying as “…a form of self-expression, a way to cope with high levels of poverty, and a tool for refugees and the children of refugees to build community among each other while simultaneously establishing roots in a new land.”⁴ However, as David Yang reminds us in his oral history, its important not to forget that ultimately “It was a bunch of kids having fun!”

Listen to oral history interviews of Bumz Crew members below:

Listen to oral history interviews of Hmong b-boys from other crews who were influenced by the Bumz below:

To learn more about Fresno's breakdancing scene, see the B-Boying and B-Girling Collection located here.

Citations:

1. N. Tapp, "Hmong," Encyclopedia Britannica, March 15, 2010, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hmong; Minnesota Historical Society, “Hmong Timeline,” Minnesota Historical Society, accessed August 4, 2021, https://www.mnhs.org/hmong/hmong-timeline; Jill Cowan, “A Closer Look at Fresno’s Hmong Community,” New York Times, November 20, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/20/us/fresno-hmong.html; Melissa Borja, “‘The New Way’: How American Refugee Policies Changed Hmong Religious Life,” The American Historian (Organization of American Historians), accessed August 4, 2021, https://www.oah.org/tah/issues/2018/november/the-new-way-how-american-refugee-policies-changed-hmong-religious-life/.

2. Abby Budiman, “Hmong in the U.S. Fact Sheet,” Pew Research Center, April 29, 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/fact-sheet/asian-americans-hmong-in-the-u-s/.

3. Lisa Lee Herrick, “Eating Thirty in Fresno: Finding Home at Hmong New Year,” Boom California, December 24, 2019, https://boomcalifornia.org/2019/12/24/eating-thirty-in-fresno-finding-home-at-hmong-new-year/.

4. Sean Slusser, “Smurfs, Wizards, and the History of Hmong B-Boy Culture in Southeast Fresno,” Tropics of Meta, March 31, 2017, https://tropicsofmeta.com/2017/03/31/smurfs-wizards-and-the-history-of-hmong-b-boy-culture-in-southeast-fresno/.